One of my favorite American writers, Willa Cather (1873-1947), put Nebraska on the literary map when she immortalized the state in several novels. I have previously reported on our literary pilgrimage to her childhood home. Thanks to my husband, who has read several books by a second Nebraska author, our recent visit to our neighboring state also included a second literary pilgrimage.

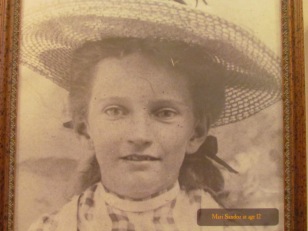

Mari Sandoz (1886-1966) was a daughter of Nebraska’s Sandhills. She grew up on an isolated homestead along the Niobrara River until the age of fourteen, when her parents moved the family to a second homestead, even more remote than the first. Her formal education ended after eighth grade, but she was a determined autodidact and lifelong learner. Following a brief marriage and divorce, she moved to Nebraska’s capital, Lincoln, at the age of twenty-two, where she spent many years, similar to Willa Cather. In another parallel, both women left Nebraska for the lure of New York.

Mari loved to write even as a child, but her parents not only discouraged her passion, they even punished her for it. When she won a prize for one of her short story submissions at the tender age of twelve, her father, Jules, a stern, opinionated, and violent man who considered writers “the maggots of society,” beat her badly, a treatment she had to endure throughout childhood. Undeterred, she continued to compose in secret, until she lived on her own. In Lincoln, while working as a teacher, she also attended classes at university, despite the lack of a high school education. And she wrote, submitted manuscripts, and suffered rejection after rejection. Reportedly, she burned seventy-plus manuscripts in 1933, before she moved back to the homestead after her father’s death, to live with her mother. Two years later, the publication of her first novel, Old Jules, ironically based on her complicated relationship with her father, was a career-turner, and the associated $5,000 award afforded her the freedom to write full-time thereafter.

Her canon includes at least twenty-one major works of fiction, non-fiction, biography, and essays, and many of her books are still in print. One of the benefits of her upbringing was exposure to Native Americans who lived in the vicinity, visited and exchanged stories with her father to which she was privy, and which caused a deep and abiding interest in and concern for the fate of the Indians. Many of her works deal with their history, such as Crazy Horse and Cheyenne Autumn. She was sympathetic to their situation, outraged at their mistreatment, and concerned for their future on reservations, and became an outspoken (outwritten) advocate for Indigenous groups.

A selection of Mari Sandoz’s publications

Several critics faulted Mari for taking liberty with history. Even though many agreed that her writing was based on actual, well-researched facts, she was censured for inventing dialogue and details to fill in the blanks; for creating overly sympathetic characters; for being exceedingly enamored with the Indigenous subjects of her stories. Her detractors might have reflected the unwillingness of a country to deal with a dark stain in its history.

Chadron State College in Chadron, about twenty miles east of Fort Robinson, houses the Mari Sandoz High Plains Heritage Center, one of our destinations during our recent trip to Nebraska. It is a fitting tribute to one of the state’s exceptional daughters, offering an honest evaluation of her life and accomplishments, but also of the controversy regarding her critical reception.

To enlarge a photo, click on it. To read its caption, hover the cursor over it.

We finished our pilgrimage by driving through the Sandhill country of Mari’s girlhood, passing near the site of the first homestead, then spending a few hours in the neighborhood of the family’s second home, which also became Mari’s final resting place.

As we sat on a bench next to her grave, overlooking the wide valley where bison and Indians once tread, where settlers put down roots, where Mari developed her talents in secrecy, where her mortal remains have mingled with Nebraska’s soil, where a gentle breeze caressed the green hills, we recalled one of the quotes highlighted at the museum: “Mari had a talent – a talent for catching and bringing to life the stories that blew across the plains like the everpresent and enigmatic wind.”

Never heard of Mari before – thank you for taking us with you on a journey to this interesting woman!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for going on the journey with me, Anna! I learned a lot, too! 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Danke für diesen schönen und interessanten Beitrag, liebe Tanja.

Auch ich habe noch nie von Mari gehört.

Ich freue mich, etwas von dieser tollen Frau hier bei dir erfahren zu haben.

Liebe Grüße

Brigitte

LikeLiked by 2 people

Herzlichen Dank für die Rückmeldung, liebe Brigitte. Unser Besuch und mein seitheriges Lesen haben mir mal wieder bewusst gemacht, wie viele faszinierende Menschengeschichten relativ obskur sind. Sei herzlich gegrüßt,

Tanja

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Tanja,

wie schön, bei dir etwas zu einer Autorin zu erfahren, die mir vor wenigen Minuten noch gänzlich unbekannt war. Da muss ich doch glatt mal nachforschen. Vielen Dank für diesen interessanten Beitrag.

LG aus dem viel zu warmen und trockenen Deutschland

Anna

LikeLiked by 2 people

Das freut mich sehr, liebe Anna. Ich weiß nicht, ob ihr Werk ins Deutsche übersetzt wurde, und wenn Du etwas herausfindest, lass es mich doch bitte wissen.

Ich hoffe die Trockenheit und Hitze enden bald, doch die langfristigen Vorhersagen sind furchterregend!

Herzliche Grüße,

Tanja

LikeLike

I’ve not heard of Mari Sandoz before. Thank you for bringing her to my attention. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad to share what I have learned about Mari, Nirmala. I have since read her novel “Crazy Horse” and am impressed with the pains she took to try to show the Indians’ point of view. It took me a little while to get used to her style, and reading the introduction definitely helped me understand the context much better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I will check if the local library has Crazy Horse. I don’t think I’ve read any books that explore the perspective of Indians.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello there. I’d never heard of Mari. I’m going to see if my local library system carries any of her works.

Your article reminded me of a book that I read years ago. I liked it very much back then (50 or more years ago): The Country Of The Pointed Firs, by Sarah Orne Jewett.

Till next time —

Neil

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds interesting, thank you for mentioning Sarah Orne Jewett. Anna

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hi Neil,

Thank you for your feedback. I hope you will find something by Mari that appeals to you. I just finished “Crazy Horse”, and “Old Jules” is high on my list. I often skip introductions in books, but in her case, I think it is helpful to read them, to gain a better understanding of the context.

I have only read an excerpt of the title by Sarah Orne Jewett you mention, but liked her descriptive language. She and Willa Cather were close friends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always admire people who are able to persevere and to follow their dreams under not so favorable circumstances!

It was a very interesting entry about a very interesting lady!

Kindes regards,

Christa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing my interest in this remarkable woman, Christa. She definitely had to overcome many odds, but in the end lived her dream. Enviable!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m reading Laura Dassow Walls’s recent biography of Thoreau. Over and over she reports how keen Thoreau was to learn as much as he could from the Indians who still remained in his part of the country. He and Sandoz (whom I hadn’t heard of, like most of your readers) had that interest in common with Helen Hunt Jackson, buried in Colorado Springs, whom we’ve discussed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw your mention of Thoreau’s biography in a recent post. It sounds fascinating. He might have been one of the few Americans interested in learning from a people who had successfully lived off the earth for ages, without destroying their own basis of life. I wonder what he would have to say today. Unfortunately, he, Helen Hunt Jackson, and Mari Sandoz were few and far between.

I appreciate your visit and comment, Steve.

LikeLike

This was so interesting. Imagine, punishing a child for creating!

I know that in the upper midwest art of all kinds was viewed with great suspicion, and attitude I still encounter today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very sad, Melissa. I think for some people who have to work hard to make a living, “dabbling” in art might seem like a waste of time, as it takes away from the tasks at hand. And it might be due to a down-to-earth attitude, because for most artists, it is hard to make a living from their art alone. But that is a generalization, of course, and different people probably have different reasons.

LikeLike

What an intriguing life she led. I’m looking forward to finding some of her works to read. Thanks for the very illuminating introduction to Mari.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing my interest in this inspiring woman. I hope you will find her work equally as inspiring.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tanja – Again, I learned something new. Interesting read and beautiful photos. I am going to have to check out her writing. Thank you so much for sharing. -Jill

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jill,

I truly appreciate you taking the time to wade through my previous posts. I loved learning more about Mari Sandoz, and I hope to read more of her books, after I finally got around to “Crazy Horse”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are most welcome. I will definitely have to check out her work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good night, Jill. Time for me to go to bed (11 PM MST). Sweet dreams.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, still MDT, for about another month…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sweet dreams to you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] PS: Thanks to my husband for coming up with this post’s title. It was inspired by author Mari Sandoz, whose books include evocative names for the different seasons used by the American Indian tribes she wrote about. I have introduced her in a previous post. […]

LikeLike