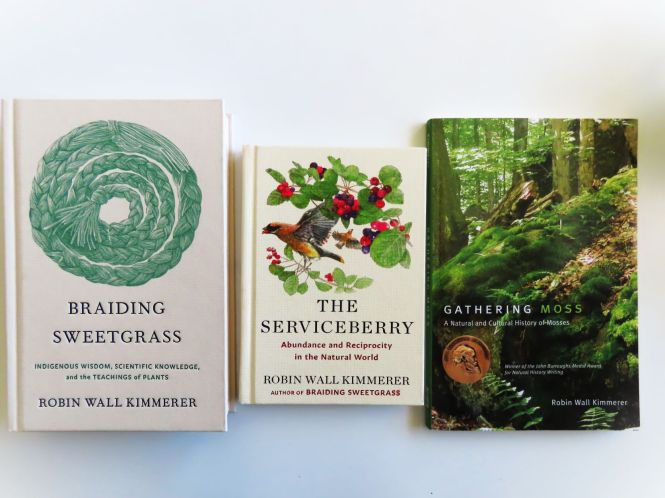

On the occasion of Earth Day 2025, I would like to talk about a book that revolves around Earth and puts Earth at the center, espousing a geocentric world view of sorts. If you are familiar with my blog, you might remember how deeply I have been touched by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s writing. I have previously introduced her books, the lesser-known Gathering Moss from 2003 as well as her bestselling Braiding Sweetgrass, first published in 2013. When I learned of the publication of a third last autumn, I bought copies for myself and a few friends (“sharing the same book is a literary kinship”). I finished reading The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World for the second time not long ago and would like to share some impressions and quotes. Please bear with me. As always, when it comes to her works, I find myself marking and copying entire pages.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. As an Indigenous individual and scientist, she has unique insights which she shares in her writing and teaching as SUNY Distinguished Teaching Professor of Environmental Biology, as well as through the Center for Native Peoples and the Environment, which she founded.

Robin’s writing is suffused with a love and appreciation for Earth. One of the recurring themes is that life and survival depend completely on the myriad gifts Nature bestows on all living beings, be it air, water, or food. Receiving those gifts should lead to gratitude. Instead, not only have we taken these gifts for granted, we have also acted as if there were no tomorrow: clearcutting forests, draining wetlands, decimating animals and plants to or beyond the brink of extinction, polluting our air and water, burning fossil fuels regardless of the consequences. We have taken, taken, taken, without giving much—if anything—in return.

Robin reminds us that gratitude is the natural response to receiving gifts, and that gratitude results in a desire for reciprocity, for returning gifts to the giver. I’m sure all of us can think of myriad ways to show our appreciation for Earth’s gifts, and for giving something in return. This “something” might consist of:

- planting native plants in order to support local fauna and to counteract the loss of trees to indiscriminate logging or wildfires

- refraining from the use of herbicides or pesticides (which are mostly undiscriminating biocides)

- using less plastic

- recycling

- coming up with other ways to lower or offset our carbon footprints (eg. by driving our cars less and less aggressively, by flying less, by committing to alternative energies)

- And last but not least consuming less! Of everything! In a closed system with a mushrooming human population and finite resources, it’s impossible to keep using more and more.

These are some steps each of us can take, and bears a responsibility to take.

The author suggests that it’s helpful to foster a sense of gratitude for everything we have, a mental attitude also reflected in the widely known “Count Your Blessings” mindset.

Enumerating the gifts you’ve received creates a sense of abundance, the knowing that you already have what you need. Recognizing “enoughness” is a radical act in an economy that is always urging us to consume more (my emphasis).

To illustrate the workings of reciprocity, she uses the example of serviceberries. They feed birds and humans alike, giving freely of themselves. In so doing, they perpetuate their own existence (all those delicious berries gobbled up by the birds are being deposited as seeds to foster the next generation). Robin calls this natural system of mutual give and take that benefits all the “gift economy.” She has alluded to this concept in her writing before but in The Serviceberry, she compares and contrasts it to the market economy most of us have grown up in, and grown accustomed to. It is based on the assumption of scarcity of resources which must be exploited, hoarded, and commoditized (by a few), before they can be meted out (to the many) for a profit.

Robin shows how this attitude has led to the uncontrolled exploitation of Nature which has brought us to our present reality: a world and climate in crisis with the resultant distress of all earthlings, be they plant or animal, including humans.

When something moves from the status of gift to the status of commodity, we can become detached from our mutual responsibility. We know the consequences of that detachment. Why then have we permitted the dominant economic systems that commoditize everything? That create scarcity instead of abundance, that promote accumulation rather than sharing? We’ve surrendered our values to an economic system that actively harms what we love. Our metrics of economic values like GDP count only monetary value in the marketplace, of that which can be bought and sold. There is no place in these equations for the economic value of clean air and carbon sequestration and the ineffable riches of a forest filled with birdsong (my emphasis).

I’m sure many of us have had the same question Robin poses so poignantly:

When an economic system actively destroys what we love, isn’t it time for a different system?

Let’s remember that the “System” is led by individuals, by a relatively small number of people, who have names, with more money than God and certainly less compassion. They sit in boardrooms deciding to exploit fossil fuels for short-term gain while the world burns. They know the science, they know the consequences, but they proceed with ecocidal business as usual and do it anyway.

One approach to addressing our problems is by changing our attitudes as well as our actions:

Imagine the outcome if we each took only enough, rather than far more than our share. The wealth and security we seem to crave could be met by sharing what we have. Ecopsychologists have shown that the practice of gratitude puts brakes on hyperconsumption. The relationships nurtured by gift thinking diminish our sense of scarcity and want. In that climate of sufficiency, our hunger for more abates and we take only what we need, in respect for the generosity of the giver.

In a gift economy, wealth is understood as having enough to share, and the practice of dealing with abundance is to give it away. . . . A gift economy nurtures the community bonds that enhance mutual well-being; the economic unit is “we” rather than “I,” as all flourishing is mutual (my emphasis).

If you are convinced that egotism and striving to get ahead of everybody else is ingrained in our DNA, consider the following:

Competition between individuals or success was long seen as the driving force in ecology and in economics. Science, politics, and economies were entangled in adopting metaphors from the natural world that reflected as much about social attitudes as about ecological reality. But that approach has been increasingly questioned and scientific evidence is mounting that mutualism and cooperation also play a major role in evolution and enhance ecological well-being, especially in changing environments. Mutualism or reciprocal exchanges create abundance for both partners, by sharing (my emphasis).

The author gives examples of individuals and groups who are trying to embrace a gift economy with free farmstands, freecycling, repair cafés, clothing swaps, campus free stores, money-free work exchanges, cooperative farms, peer-to-peer lending, to name a few.

We live in the tension between what is and what is possible. On one hand, we can witness the reciprocity of the economy of nature, showing us how things are supposed to work. And on the other, we see the outcomes of extractive capitalism, breaking every facet of “natural law.” I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling despair in that comparison and my powerlessness to change it. In illuminating these alternatives, people have the courage to say, “Let’s create something different, something aligned with our values. We don’t have to be complicit.”

It is heartening to me that all these grassroots innovations are arising, creating to resist the economic systems that are destroying what we love by making new systems founded on protecting what we love. I have a newfound affection for the language we use. It seems apt that we call these “grassroots” movements, emulating the gift economy of plants.

Even though Robin is a visionary, she is also a realist:

I don’t think market capitalism is going to vanquish; the faceless institutions that benefit from it are far too entrenched. The thieves are very powerful. But I don’t think it’s pie in the sky to imagine that we can create incentives to nurture a gift economy that runs right alongside the market economy.

The author concludes with the following paragraph:

Regenerative economies that reciprocate the gift are the only path forward. To replenish the possibility of mutual flourishing, for birds and berries and people, we need an economy that shares the gifts of the Earth, following the lead of our oldest teachers, the plants. They invite us all into the circle to give our human gifts in return for all that we have been giving. How will we answer?

🌎 🌍 🌎 🌍 🌎 🌍 🌎 🌍 🌎 🌍 🌎 🌍 🌎

Like all of Robin’s creations, this is an important work with an urgent message, delivered in the most eloquent of words and complemented by the most lovely of illustrations, such as the one on the front cover (see featured photo of Cedar Waxwings feeding on serviceberries above) and on the back endpaper (see photo of an American Robin gobbling serviceberries below).

My only regrets: I wish the book had been longer. And, more importantly, I wish that I and you and all those people with influence and power would take its message to heart and translate it into action, so that we can do whatever is humanly possible to help preserve our special Earth for all living things, now and in the future.

The Serviceberry saw the light of the world before the last election in the United States. The new administration represents the worst possible version of what our times and our Earth need. I suspect it’s causing Robin to lie awake at night and weep. It’s what happening to me, and maybe to you also.

It is not enough to honor Earth on a single day each year. Every day needs to be Earth Day!

Thanks for sharing, Tanja.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for stopping by and commenting, Michael. Your posts always showcase Nature’s beauty and what we are at risk of losing if we go on in the current vein.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re most welcome, Tanja. I try to showcase the beauty of nature and what we are losing with our irresponsible acts. Thank you very much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wie wahr – jeder Tag sollte ein Earth Day sein, es liegt an jedem Einzelnen von uns, genau das daraus zu machen.

Herzliche Grüße

MAren

LikeLiked by 1 person

Herzlichen Dank für Deinen Kommentar, liebe Maren. Laß uns weiterhin versuchen, unseren kleinen Beitrag zu leisten . . .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kimmerer’s writing is so powerful, there’s so much wisdom here. The good news for me is that I’ve just checked our local public library’s online catalogue, and discovered that The Serviceberry is in stock, so I shall be able to read it in its entirety. And on reflection, isn’t the public library movement itself a fine example of her principles of reciprocity, mutuality and the rejection of hyper-consumption!

And yes, your final sentence says it all, Tanja. Every day needs to be Earth Day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Mr. P.

I never fail to be impressed and touched by the insights and wisdom of Robin. And despite being very realistic and sober, she still harbors hope that we might learn to do better.

I hope her writing will speak to you.

And your assessment about public libraries being examples of a gift economy is very astute.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well-written post with many salient points, Tanja. As you know, we share the same feeling about the Earth as our Mother and the care we share about her well-being and balance. May the masses awaken during these dark times. I have faith in Nature to right our wrongs, with us or without us. 💙🌎

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for your comment, Eliza. There is some comfort in the knowledge that Nature might be able to go after humankind’s extinction. But the fact that we are responsible for the disappearance of so many other beings is devastating.

LikeLike

The earth has a long and proven history of evolution, which I trust. Ever read this book? Quite enlightening! https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_World_Without_Us

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have not read this book. Thank you for the link, it sounds intriguing. Were you more or less depressed after reading it?

LikeLike

Actually, the contrary. It gave me hope for the planet’s resiliency. Earth doesn’t need us. We’ve made such a mess of things, we might be creating our own obsolescence anyway.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s somewhat of a sad comfort to know that we are dispensable, but I have no doubt in my mind that Earth and all the more-than-human creatures would be better off without us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not that I am religious, quite the contrary, but this must have been a reason Adam and Eve got kicked out of Eden. 😉

LikeLike

Great post! happy Earth Day 🌍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, dear Luisa. Happy Earth Day every day!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are so very welcome my dear Tanja.

It’s my pleasure as always

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Tanja

Interesting economic concept that the classic anarchists tried out in Spain and the Ukraine.

Thanks for your review

The Fab Four of Cley

🙂 🙂 🙂 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Klausbernd.

It’s too bad that some of the more humane economic approaches have not succeeded on a larger scale.

One can still hope for a system that is kinder to more people as well as to the Earth.

Kind regards,

Tanja

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very fitting Earth Day tribute, thanks Tanja.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Brad, I appreciate it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tanja – recognizing “enoughness” is something we can all strive for and do even in dispiriting times such as these. Thanks for advocating for our Earth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Carol,

No need to apologise, somehow the spelling of my name miraculously corrected itself! 😊

I agree about the notion that “recognizing enoughness” is a good antidote to conspicuous and thoughtless consumption (at least for those of us who live in affluence). Sharing with those less fortunate is another next necessary step.

Let’s keep doing what we can to help support our wonderful Earth.

Tanja

PS: I didn’t get around to reading your last several posts in time to leave a comment, but I wanted to let you know that I enjoyed learning about your pelargonium and geranium flowers, as well as about the striking Bateleur Eagles. I hope the efforts at preservation will be successful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tanja – thanks. The poor Earth needs all the help it can get, especially as the onslaught against it is, if anything, escalating.

Sorry this response is so overdue! Thanks for reading my two latest blogs. I am a bit chastened to see I have only managed 2 posts so far this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Carol. It’s more than a little disheartening to know we belong to the only species that actively and consciously destroys its own world.

Life often gets in the way of blogging, it’s happening to all of us.

Kind regards,

Tanja

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Tanja. One thing we bloggers do, is encourage each other!

With best wishes from South Africa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the solidarity, Carol! 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

A great message on Earth Day Tanja, Maggie

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate your comment, Maggie, thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Until I read your fine essay, I’d forgotten that today is Earth Day. Here’s to Planet Earth!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Neil. Yes, here is to Earth. Today and every day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Liebe Tanja,

die Bücher von Robin Wall Kimmerer sprechen mich sehr an!

Auf Deutsch sind sie beim AUFBAU Verlag erschienen. Da werde ich mich gleich einmal beim AUFBAU Verlag um ein Rezensionsexemplar von “The Serviceberry” (der deutsche Titel lautet: “Die Großzügigkeit der Felsenbirne”) nachfragen.

Hab’ Dank für Deine engagierte Empfehlung dieser Bücher.

Herzlich grüßt Dich

Ulrike

LikeLiked by 1 person

Danke für Deinen Kommentar, liebe Ulrike.

Es freut mich, daß Robins Bücher ins Deutsche übersetzt wurden, das war mir bisher nicht bewußt. Danke für diese Information.

Ich hoffe, daß Dich ihre Lebensphilosophie ansprechen wird und daß die Übersetzung gut gelungen ist. Ihr Stil im Englischen (bzw. Amerikanischen) ist elegant und trotzdem bodenständig.

Herzliche Grüße zurück,

Tanja

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a wonderful post for earth day. I have been looking forward to reading “The Serviceberry” for awhile now and this book review is inspiring me to read it sooner than later. I too lay awake nights worrying about the state of the world but I think reading this book can help us nature lovers feel less alone and provide a way forward. 💚

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Julie. If lying awake would only help make the world a better place. But since it does not, we need to try to find other ways in our personal lives to make a difference. Sometimes it feels like a drop of water in a vast ocean, but it’s better than doing nothing.

I hope you will enjoy reading “The Serviceberry.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure I will enjoy it Tanya.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am sure also, Julie, especially since you liked her other books. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amen! Another way to phrase it is with the word “generosity,” which I place a high value on. And despite the greediness of those at the top, I see generosity all around me. Is it enough? I don’t know. But it’s something.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Laurie. Generosity is definitely inherent in Nature’s many gifts–and in the acts of many people. The discrepancy between our potential to do good and all the bad in the world is exasperating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sure is!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this review and for introducing this author. I’m not familiar with her work, but her books are now on my ‘must read’ list. Just out of curiosity, does she also draw the illustrations?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Tina. I imagine that Robin Wall Kimmerer will speak to your soul as well.

I don’t think she does her own illustrations, she leaves that to some of her gifted friends or family.

LikeLike

What a beautiful philosophy. I also think it applies to all lands with their native peoples. “The Serviceberry” is a lesson which Donald Trump should also read, however, I don’t think it’s in him to be cultured in any way but in ambition and ostentation, in a constant self-righteousness display! I pray for the USA and the good people that are against him!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Maria. It’s incredibly frustrating because we know what needs to be done to mitigate climate change, yet we seem unwilling or unable to translate that knowledge into action.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Translating the message into action is the key, if we want be successful in our fight against the destruction of. the environment. Thank you for the book review, dear Tanja!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, dear Peter. You are absolutely right. Just talking about what needs to happen is not enough.

LikeLike

An excellent post for Earth Day and good food for thought. I agree that it’s time for a new system. The old one is destroying the Earth and the life upon it. I do see small signs of hope here and there, like the starting of ‘community gardens’ over here, where people work together to enhance the natural environment and produce food for those in the community, especially the most needy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Ann.

I like the idea of community gardens. Not only do they provide for people in need, they help educate about how food is grown and healthy food choices.

Let’s hope that all the things that are happening on a small scale will add up and make a difference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for sharing the works of Robin Wall Kimmerer, especially her newest book. I humbly feel it is a humble contribution to Earth Day and will see if I can get a hold of her books here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, dear Takami. I think you would enjoy Robin’s writing and her profound and caring world view.

LikeLike

Liebe Tanja,

das sind tolle Gedanken! Undankbarkeit geht oft einher mit Egoismus, die Gier nach mehr, Geiz, Neid und Missgunst. Wie viel besser könnten wir leben, wenn Dankbarkeit unser Handeln leiten würde. Es sind nur wenige Unternehmen an der Weltspitze, die aber massiv auf alle Menschen einwirken, weil sie unsere Lebensgrundlagen rücksichtslos und gewinnorientiert ausbeuten. Dennoch kommen wir als Einzelne etwa tun. Und das fängt mit unserer Denkweise an.

Danke für das Teilen!

VG Simone

PS: Ich weiß nicht warum WP immer mal wieder das Folgen bei Dir abschaltet 😕

LikeLiked by 1 person

Herzlichen Dank für Deinen Kommentar, liebe Simone. Mit allem was Du sagst hast Du recht. Auch wenn es manchmal so scheint, als wären unsere individuellen Entscheidungen und Lebensstile umsonst, müssen wir trotzdem versuchen, so rücksichtsvoll wie möglich zu leben. Hoffen wir mal, daß es einen Unterschied macht.

Es tut mir leid, daß WP Dir Probleme bereitet.

Sei herzlich gegrüßt.

Tanja

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfamiliar with the serviceberry, I looked it up and was led to the genus Amelanchier, about which Wikipedia notes that “at least one species is native to every U.S. state except Hawaii and to every Canadian province and territory.” Many fruits and berries are of service to people and animals, so I got to wondering how this genus got singled out for a name with service in it. I asked Google the question and got an AI answer:

“The serviceberry got its name because its blooming period in early spring coincided with the thawing of the ground, making it possible to bury the dead and hold church services in remote settlements. The plant’s early bloom was a sign of winter’s passing and a signal for itinerant preachers to travel and serve the communities.”

I looked further and found a website that makes a convincing case that that story is folk etymology, which is to say false etymology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Steve. Interestingly, WP asked me to approve it, which is not how things usually happen. Maybe because you included the link, though that was never a problem before.

This is how Robin Wall Kimmerer describes the significance of serviceberry:

“Saskatoon, Juneberry, Serviceberry–these are among the many names for Amelanchier. Ethnobotanists know that the more names a plant has, the greater its cultural importance. The tree is beloved or its fruits, for medicinal use, and for the early froth of flowers that whiten woodland edges at the first hint of spring. Serviceberry is known as a calendar plant, so faithful is it to seasonal weather patterns. Its bloom is a sign that the ground has thawed. In this folklore, this was the time that mountain roads became passable for circuit preachers, who arrived to conduct church services. It is also a reliable indicator to fisherfolk that the shad are running upstream–or at least it was back in the day when rivers were clear and free enough to support the spawning of shad.

Calendar plants like Serviceberry are important for synchronizing the seasonal rounds of traditional Indigenous People, who move in an annual cycle through their homelands to where the foods are ready.”

One could take issue with the generalization that folk etymology is false etymology.

LikeLike

If I remember right, I originally included two links in the comment, which is a trigger for WP to require approval in an attempt to keep out spam. I’ll conjecture that I must have removed one of the links, but only after WP had already set a flag on the comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wasn’t aware of that, thank you for letting me know.

LikeLike

I am continually perplexed by the critical concepts that get only a single day of national reflection versus those that are a month long.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had never thought of it that way, but that question would be worth a discussion.

For me, with regard to earth, every day needs to be Earth Day. Without a healthy, liveable earth, nothing else matters.

LikeLiked by 1 person